|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||||

|

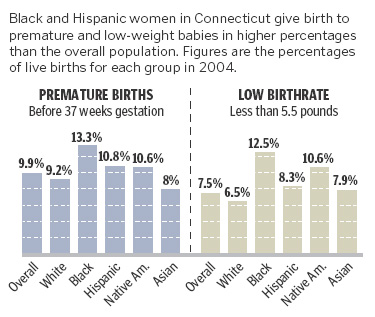

A Test Case On Pregnancy Issues Goal Is Better Health For City's Women And Babies December 21, 2006 For decades, cities such as Hartford have struggled to safeguard the health of newborns, especially those born to low-income mothers. But despite modest improvements, the efforts have not always been successful.

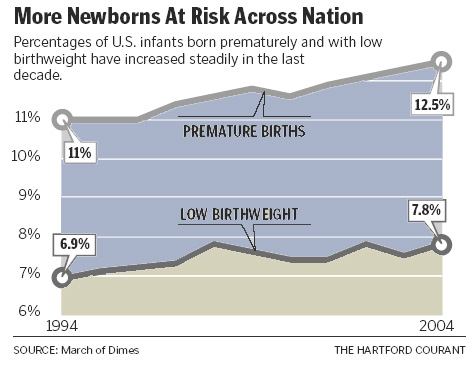

More babies are being born too early and too small, setting them up for the prospect of lifelong struggles. Some will endure devastating disabilities. Others will have more subtle social, emotional or learning deficits. Hartford, Nashville and Los Angeles were chosen for an experiment funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention designed to help women prepare for pregnancy long before they even consider having a baby. "Many women are already at risk by the time they are pregnant," said Magda Peck, the project coordinator. "Prenatal care, frankly, comes too late." Peck is the founder of City Match, a think-tank based at the University of Nebraska that helps city health departments share information about the best practices in improving maternal and infant health. The CDC gave Peck $100,000 to help the three cities coordinate health services to women before, between and beyond pregnancies. Although there is no scientifically proven way to prevent premature births, the strategies are based on the little scientists do know. For example, while folic acid can prevent certain birth defects, only one-third of women take vitamins containing the supplement daily. Women with uncontrolled diabetes are three times more likely to have a baby with a birth defect than women without the condition, yet many city residents do not even know they have diabetes. Smoking, obesity and certain medications to control chronic diseases also can put women at risk of a bad birth outcome. "There is a strong body of data that is able to link women's health to the health of their babies," Peck told a group of Hartford public health advocates who gathered this week to kick off the trial. The funding will mainly pay for training health care and social service providers. It will then be their job to figure out how to best encourage women to get into good shape before they decide to get pregnant. In some ways, the effort seems Herculean. While Hartford offers a wealth of health and social services to low-income women, the programs are fragmented and uncoordinated, said Ramon Rojano, the city's director of health and human services. After the first meeting with representatives of City Match and the CDC this week, Leticia Marulanda, manager of maternal and child health in Hartford, said she was a bit overwhelmed by the responsibility of coordinating the pre-pregnancy project. "My other projects," which include lead screening, oral health and immunization for children, she said, "are going to suffer." Access to care is a also major issue. While Medicaid covers almost unlimited care once a woman becomes pregnant, many women have no coverage before they are pregnant. Another problem is that discovering real solutions to prevent premature births remains one of medicine's most vexing mysteries. Every time researchers come up with a likely culprit, science debunks it. The latest disappointing finding was published last month in the New England Journal of Medicine. Doctors thought they had seen an association between maternal gum disease and premature and low-weight birth. The evidence seemed so strong that at least one insurance company started paying for dental care for its pregnant members. But researchers found no difference in birth outcomes between a group of pregnant patients who were given intensive dental care and those who did not get their teeth cleaned. But the costs of prematurity are, nonetheless, clear. In a report released last summer, the Institute of Medicine estimated that premature births cost the United States at least $26 billion a year, including the cost of medical care, early intervention, special education and lost household productivity and income.

|

||||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||||

|