|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

Change Rattles Asylum Hill As Developer Rehabs, Tenants Displaced July 15, 2007 Jennie Camerato shook her cane for emphasis, saying she's lived in her brick home on Hawthorn Street for 54 years and isn't selling unless the price is right. She wasn't even a little swayed by the guy who offered to come over every day, take her for a walk, and make her homemade chicken soup.

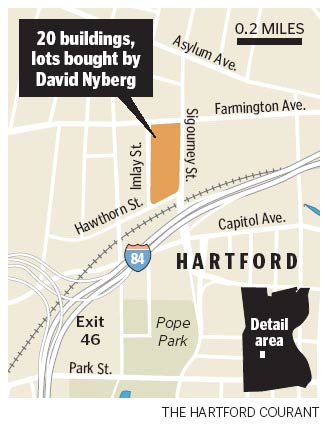

"I may be old, but I'm not stupid," Camerato said. Developer David Nyberg had just spent more than $11 million to buy more than a dozen apartment buildings with 250 units in Asylum Hill. He wants to spend roughly the same amount to rehabilitate and upgrade those apartments. And he would like to add the building where Camerato lives to his collection. The Asylum Hill project is out of character for Nyberg, a New Haven developer known in Hartford for turning old buildings into new apartments and condos. But Nyberg said the move makes sense. Hartford's leaders are trying to take the investment in downtown beyond downtown itself. And Asylum Hill is a neighborhood reaching for a resurgence - near downtown, on the way to West Hartford, and with the newly opened Connecticut Culinary Institute, insurance companies and the St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center in its broad backyard. "Students, young professionals, the custodian at St. Francis - I'm thrilled, I'd be excited to have that resident," Nyberg said. But Nyberg's offers of cash to get people to leave - and his refusal to renew leases - has stirred community concerns that Nyberg is, in the short term, displacing tenants and, in the long term, trying to trade working people for a more upscale crowd. He said neither is true, but Asylum Hill has been here before. When the neighborhood bottomed out in the 1970s, new private investment stirred fears of displacement, and not without good reason: Gentrification in other cities has squeezed people out of their homes. It's a story repeated nationwide, an inescapable byproduct when a young developer comes to an old block in a poor city with ambition. Casting A Wide Net Nyberg sat at the wheel of a company Ford pickup in suit pants, cufflinks, dress loafers - no socks - and his jacket in the back seat. At 36, he listens to 1980s Michael Jackson and isn't shy about it. He is one of downtown's younger developers, a man with a reputation for building without using public money. He turned the old SNET building on Bushnell Park into apartment units called 55 on the Park; he turned the old HELCO building into condominiums called The Metropolitan; he's working to turn the old American Airlines building at 901 Main St. into condos. Some things have gone well; others, like the Metropolitan, just OK. "I blew it," he said of the latter. The units aren't selling as fast as they should have, and he missed the investor market. "The lesson is, I had 42 sold and I couldn't get them to close." His latest plan is to take the roughly 250 apartments he's just bought on Imlay Street, Niles Street and Farmington Avenue - including the complex known as the Hartford Gardens - and remake them with new electrical and water systems, new landscaping and increased security. The renovations have already begun. Nyberg walks his projects with the eye of someone who knows the work his workers do. He knows that painting hallway walls two colors with molding in the middle makes touch-up painting easier. He hates it when he sees new sod on the ground that turns brown because someone didn't water it. On a swing by Niles Street, he showed off an apartment complex that he said used to be menacing. The building is included in Nyberg's $11.28 million purchase in April. He's since rehabbed the inside and spruced up the outside - knocked down some exterior walls, hung decorative shutters, put in landscaping. "I wish you saw this before. There was graffiti, syringes; it was grates on the windows," he said. "You tell me how bad a person I am when I was initially just going to sell this." Next up are buildings on Imlay Street, where his plans include new water systems, new wiring, carpets, heating, air conditioning and security cameras. Nyberg conceded that he hopes rents will go up when the work is complete, but he knows they will be dictated by the market. He is, after all, in the real estate business, he said. To fill his buildings he's casting a wide net - one to catch some of the types of people who rent from him now, and probably some who don't. "I'm talking to everybody. I'm calling Trinity, UConn Law, the University of Hartford, the culinary institute, the hospital," he said. "I'm willing to create quality housing at a reasonable price up and down Imlay and Farmington. I want to do something special here." But before he can, he'll have to deal with the tenants who already live there. He needs them to move so he can renovate efficiently. He's not renewing expired leases, he's offering money for people to leave before their leases expire and he says he'll help tenants move to other apartments he owns and give them leases there. "I'm not going to throw somebody out on the street," he said. "It's not what I do." `I Just Don't Want To Move' But people are concerned. A sign outside the door at a community meeting gave a good sense of how it would go: "David Nyberg may own our building, but this is our home." Neighborhood residents had come together, rallied by community organizers at Hartford Organizing for Power & Equality, and wanted to air their complaints with the way Nyberg's company - College Street LLC - had handled the project. Inside, more than three dozen people gathered in a room at Asylum Hill Congregational Church Tuesday for a gripe session, pep rally and political pressure pot all in one. "Why are we here?" asked Martha-Rea Nelson, hovering over Mayor Eddie A. Perez. "We're here because Imlay, Farmington Avenue and Niles are saying enough is enough is enough. And we hope that when you say you're going to build a better Hartford, that that includes the tenants who already live here." That drew applause. Perez sat at the front of the room, listening as tenants told how Nyberg's apartment manager wouldn't take their rent, asked them to move on short notice before their leases were up and offered them varying sums of money to leave early. Perez didn't take sides, but promised to work toward a solution. The residents' stories sounded similar. Josephine Kessler lived for 20 years at 58 Imlay St. and then, for the past 27 years, in a one-bedroom apartment at 54 Imlay St. She used to like it because it was close to work at The Hartford, where she worked for 32 years; now she likes it because it's close to the bus. "Everybody's nice in the building," Kessler said. "I just don't want to move." But that didn't matter much when the building manager came knocking. Kessler's lease had expired June 1. "She says, `We're not renewing your lease anymore, you've got to move and get out,'" Kessler said. "I said, `What? Where am I going? I never did any moving in my life.'" But the apartment manager was insistent. "`You gotta go, you gotta go,'" Kessler quoted her as saying. "I told her, I said, `I've been living here for over 27 years and I'm not moving anywhere. I want to talk to the owner.'" Then the building manager went down the hall to speak with Kathie Cox, who has lived at 54 Imlay St. for 14 years. May 30 was the day, Cox recalled. Her $535 monthly lease, which includes parking, heat and hot water, wasn't going to be renewed and she had until Aug. 31 to leave, the manager told her. "She said to me that if I can get out before Aug. 31, [Nyberg would] give me $1,500," Cox said. "It was not in writing, nothing was in writing. Just word of mouth. "That's not the way it's supposed to be done," she said. Samantha Cote said she got much the same treatment and wondered why things were handled this way. She also wondered why it's happening at all - why a perfectly good working-class neighborhood has to change. "There's so many higher-end apartments in downtown, I'm not sure why they have to creep into other areas of Hartford," she said. Uphill And Downhill Asylum Hill goes in cycles. From Michael Grant's perspective, it's a neighborhood on the upswing. He said he manages roughly 400 units in the neighborhood, none of them in Nyberg's project. Downtown, high-end developments haven't had much of an effect on Asylum Hill rents, Grant said. That said, rents have gone up 20 to 30 percent in five years. Still, his average tenant works in the service industry, making roughly $10 to $13 an hour, he said. And Grant's good news for tenants is that there is still room for the working class. "With a 10 percent vacancy rate, there's certainly enough absorption to handle any displacement that one landlord who's purchasing [250] units may cause," Grant said. Longtime resident and former city Councilman Michael McGarry knows the neighborhood well. "Never quite made it," he said. "It's gone uphill, it's gone downhill several times since I've been involved." By uphill, McGarry means a "modest gentrification." By the time he bought a home there in the mid-1970s, the neighborhood had bottomed out, and the insurance companies next door came in to help. That spurred an upswing during the late 1970s and early 1980s, as new homeowners like McGarry saw the old, rundown housing stock as an opportunity. "The insurance companies decided to try to save Asylum Hill again, to bring it back to what it was, or stabilize it," McGarry said. "There were abandoned houses, rooming houses everywhere, crime, drugs, everywhere." But that effort failed by the late 1980s amid a plunge in real estate values. McGarry's house started to lose $1,000 a week in value. What was once valued at $160,000 went down to $119,000 when he sold it. After that, it went down even further. Now, with a potential upswing on the horizon, Daniel and Tiffany Franceschi are concerned about what's happening in their neighborhood. They live in one of Nyberg's recently purchased buildings at 210 Farmington Ave. Daniel works in security, patrolling the downtown city streets. But he says he can hardly afford to pay his rent now. They're looking to move to the South, he said, because the changes in the city he was born in seem to favor the wealthy instead of the working. "What's that about?" he said. "What about us?"

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|