|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

In The Hot Seat

Hartford Police Chief Patrick J. Harnett strides into the conference room at police headquarters with the imperious demeanor of a college professor preparing to grill students on a final exam. Only in this case, the students are members of Harnett's top command staff, and the questions he's firing at them have ramifications for thousands of city residents. "Whaddaya got your conditions team doing, Jose?" Harnett asks Capt. Jose Lopez in his thick New York dialect. Lopez, standing behind a podium across the room, tells the chief what his officers are doing to reduce crime in his South End district. Harnett peppers him for details about trends in burglaries and robberies. Harnett, who marks his first anniversary in the chief's job on Tuesday, is in his element here in the weekly ritual called "Compstat." With his top deputies beside him, Harnett, 61, can't get enough of this stuff - breaking down the latest crime statistics that are projected on two large screens behind the podium. As one of the reformers who helped

revolutionize urban policing by developing the Compstat system

in the New York Police Department in the 1990s, Harnett has great

faith in the ability to fight crime by dissecting numbers, neighborhood

by neighborhood and block by block. The numbers give him the

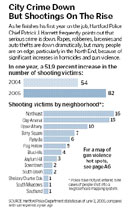

ammunition to boast that crime is down 12.6 percent overall in

Hartford so far this year. While Harnett is reassured by the numbers, many residents and department critics feel otherwise. They worry about violent feuds between young people and petty disputes too often settled by gunfire. They're troubled by brazen shootouts and a growing culture of fear and retribution on many street corners. |

Mapping Gun Crime (PDF file, 1 page)  City Crime Down But Shootings On the Rise (PDF file, 1 page) |

|

And they're alarmed that from Jan. 1 to June 11 this year, there have been 11 murders, compared with six during the same period in 2004 - a jump of 83 percent. As of June 11, the number of shootings has risen from 49 last year to 75 this year, a 53 percent increase, while the number of people shot has risen from 54 to 82 - a 52 percent increase. Instead of watching computer screens to get a feel for city crime, Harnett's critics say, he would do better checking out the sidewalks on Colebrook Street, Madison Street, Bedford Street and Seyms Street, where bloodstains can still be seen from a series of recent shootings and beatings. "I don't see a big improvement in public safety. If anything, it's gotten worse," said Steven Harris, a former city council member who is active in the North End, where much of the recent gun violence has taken place. Harris repeated a criticism of Harnett that the chief has heard often in his first year, namely that he has not fully appreciated how different Hartford is from New York, where he spent more than three decades with NYPD. "He's making the same mistake that a lot of people make when they come here from somewhere else, especially a large city like New York," Harris said. "He came in here and probably thought, hey, this is Hartford. It's a small, manageable city. How hard can it be? But Hartford is a tough place to be chief exactly because it's small. The politics are fierce, and the people are strong. They aren't going to roll over just because you're from New York." Vintage Harnett The city's gun violence crisis has become Harnett's greatest challenge. A Bronx native, Harnett was hired last year by Mayor Eddie A. Perez in large part because of his NYPD pedigree. After earning notice as an aggressive narcotics enforcer, Harnett rose to become part of the much-celebrated cadre of NYPD reformers under then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and then-police Commissioner William Bratton, Harnett's philosophical mentor. Though he's aware of criticism, Harnett said he does not let it shake his faith in the direction he's taking the department. As a disciple of the community policing philosophy that helped restore law and order to New York City, Harnett has introduced a plan in Hartford that comes from the same playbook. His neighborhood policing plan, introduced in February, divided the city into four patrol districts with officers and supervisors responsible for reducing crime in their respective zones. Harnett believes in holding his commanders accountable for their zones and empowering them to take the steps they need to fight problems as they arise. On this day at Compstat, Lopez tells Harnett that robberies and burglaries are decreasing in his zone. He had one burglary and two robberies in the past week. After questioning him for details of each of the cases, Harnett lets Lopez sit down as the next captain approaches the podium. "Whatever you're doing, it's working," Harnett tells Lopez. "But don't get too comfortable or feeling too good about your numbers. It can always change." The comments are vintage Harnett, complimentary yet cautionary, with a heavy emphasis on statistical results. The Bratton regime in New York City won widespread acclaim for its weekly grilling of neighborhood commanders during Compstat meetings, but many residents and community leaders in Hartford said Harnett should not expect similar reviews here. "I don't know what the police do in their building, but

I know people are losing faith in them on the streets," said

the Rev. Donald Johnson, a North End community activist. "That

plan sounds all well and good when you assign officers to patrol

our neighborhoods, but it won't do a damn thing if they don't

get out of the car and introduce themselves to us." "For too many people in this city, the police are viewed as an occupying force," Davis said. "We hear a lot about the chief's plan, but it hasn't really taken hold, and it won't until officers stop viewing their relationship with the community with an us-vs.-them mentality." Harnett said he understands the community's concerns, but stressed that residents should withhold judgment for at least a few more months until his plan can be fully put in place. "I think there's some impatience out there," he said. "I understand that. But the plan ... is only 4 months old. The problems we're trying to solve took years to evolve, and the solutions won't come with a magic bullet." Cracking Down Many police critics say the department's relationship with the community was dealt a crippling blow May 7, when an undercover Hartford police officer shot and killed a city teenager and shot another man in the chest. The slaying of Jashon Bryant, 18, who is black, by veteran Officer Robert Lawlor, who is white, outraged many people in the largely African American neighborhoods of the North End, who have long viewed police with suspicion. Hartford police are continuing their investigation into the shooting, which occurred, Lawlor said, because he thought Bryant was reaching for a gun. No gun has been found. Widespread concerns by residents about the probe's objectivity recently led Chief State's Attorney Christopher Morano to transfer supervision of the investigation from Hartford State's Attorney James Thomas - who has worked closely with HPD - to Waterbury State's Attorney James Connelly. Connelly could also decide to take the case out of the hands of Hartford police and hand it to another law enforcement agency. Harnett won points with some people in the North End when he went to Bryant's funeral at the request of Bryant's father. The chief appeared awkward when he walked into the church that day, but he hugged Bryant's relatives and offered his condolences before sitting next to Assistant Chief Darryl Roberts, who was born and raised in the North End, for the service. "Whatever the circumstances, the fact that this family lost this young man is a tragedy," Harnett said at the time. "We wanted to let the family know we sympathized with that loss." Harnett defended the professionalism of the detectives assigned to the Bryant investigation. "We're fully capable of conducting a thorough review, but because of the perceptions out there, I would not disagree with a decision to have another agency investigate," he said. Harnett said the growing amount of gun violence, especially in the North End, will be addressed in a new initiative he plans to present in about a week. In the meantime, he said, his policing plan includes the creation of task forces, which have been in place for a month and a half, to crack down on the city's gun and drug trades. Lawlor was working alongside a federal agent as a member of the new gun task force when he shot Bryant and the second man last month. After a year on the job, Harnett said he has been surprised by the level of scrutiny his department receives, both in the media and from community groups. "It's been a surprise, an adjustment, yeah," said Harnett, who did not do much community work in New York despite his position as a department chief. "I certainly didn't take this job because I crave the limelight, but I realize in many ways I'm the face of the department, so it's important to get out in the community and meet people. And I think I've done that." Harnett has his supporters. Temple Shannon, a community leader in the Blue Hills neighborhood, said she and her neighbors have been pleasantly surprised to see more cruisers patrolling their streets. "These officers are assigned to work only in our neighborhood, so we can really see the difference," Shannon said. "Problems we've always had, like cars parked in the yards and noise, are now being enforced. It's made our quality of life a lot better." Harnett also has the strong backing of Perez, who selected him despite widespread public support for former acting Chief Mark R. Pawlina, who now works as one of Harnett's assistant chiefs. Perez acknowledged that the increase in gun violence, as well as the Lawlor shooting, have strained the department's relationship with some residents, but he emphasized that Harnett has laid the foundation for a more responsive, professional department. "He's done exactly what I expected him to do, which was get his hands around the department and empower the command staff with an overall vision that demands accountability and results," Perez said. "In spite of the shootings, I think there are a lot of people out there who are confident he's doing the right thing." Resident Jackie Maldonado said she is not convinced Perez and

Harnett are making a difference, but they are not the only ones

to blame for the city's troubles. Challenges, Challenges Harnett and Perez are being dogged by an ongoing legal battle with a group of activists over a 32-year-old federal consent degree that demanded more civilian oversight of the department and greater sensitivity to minority residents. Both men have had to testify in federal court about how much attention they were paying to a recent court order that grew out of the 1973 case, and in doing so, they have contradicted one another at times. Perez said he and Harnett have not worked closely with the plaintiffs in the Cintron vs. Vaughn case because it has become "politicized." The group of watchdogs, which includes former Deputy Mayor Nicholas Carbone, is vehement in its criticism of the chief and mayor, saying they have ignored the recent court order. Carbone said he has been disappointed by Harnett's tenure so far. "I have no confidence in him," he said. Harnett is also facing a continuing battle over his certification as a Connecticut police officer. Because he was retired from the New York force more than three years before assuming the Hartford job, Harnett was ordered to undergo the same 600-hour regimen of training that all new officers must take to work in Connecticut, including several physical training courses. Harnett and Perez are fighting that order by the state Police Officer Training and Standards Council. The council plans to meet this week, when Harnett is expected to receive a drastically reduced order to undergo a minimum of 16 hours of training in Connecticut law, said Thomas Flaherty, the council chairman. Harnett was on the job only a few weeks when he had to deal with several disciplinary issues, including an allegation that a white supervisor ordered officers to arrest any members of minorities who were spotted walking downtown in the pre-dawn hours. Though the racial profiling allegation was not substantiated, Harnett demoted the supervisor for a pattern of retribution against officers who disagreed with him and streamlined the system by which residents file complaints against officers. While Harnett is viewed as a cop's cop by some, other Hartford officers are less than enthusiastic about him. Richard Rodriguez, the president of the police union, said the chief's new policing plan is not much different from similar plans adopted by previous chiefs. He said the department historically has broken down the city into different districts, usually without success. "Is it better than doing nothing? Yes. Was it well thought out? No," Rodriguez said. "I would give him a C-minus so far. He needs to communicate more, not only with the public, but with his own officers." Rodriguez said the chief's plan would work better if the department had more officers to deploy in the various zones, which was a key to the philosophy's success in New York. Right now, the Hartford force has 430 sworn officers, up from about 400 a year ago. "We have so many officers running around, going from call to call, they have no time to get out of the car to meet people," Rodriguez said. Harnett disagreed that his management style tends to be bureaucratic and removed from people. And he is convinced that his plan can effectively be carried out with the number of officers he has now. "I try very hard not be aloof, and I think there are a lot of people in the community who can attest to that," he said. "There are always going to be critics, but I think for the most part I've been able to work well with the people here. I enjoy sharing success with them." Besides acknowledging the political and professional challenges of the job, Harnett said it has also taken a personal toll. His wife of 38 years, MaryAnn Harnett, continues to live in their home in New York state, while he lives in an apartment in Hartford. "She's made a lot of sacrifices over the years, and this is no different," said Harnett, the father of five grown daughters. "She knows this is what I am, this is what I do, but I miss her and my children and my grandchildren." Asked how long he plans to stay in Hartford, the chief said he had no clear exit strategy in mind. "I want to stick around long enough to see the work that

we're doing begin to show results," he said, "but I

won't be here forever.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 | |

||

|