|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

FIRST OF TWO PARTS Ten young men graduated from Prince Tech's electrical shop

five years ago. Today, there isn't a licensed electrician among

them. In some ways, that failure is a failure of their school,

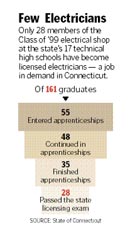

and a consequence of the global marketplace. Five years ago, 10 cocky young men graduated from Hartford's Prince Tech, armed with high school diplomas, three years of vocational education, and the expectation of lucrative careers as electricians. Inside their ramshackle trade shop, they had studied the National Electrical Code, muddled through load calculations, wired the school's new welding shop and come to know each other like brothers. As technical high school graduates, they thought they would easily land jobs in a field that was in demand and where salaries started at about $24,000 a year. "They were a good group of boys," said Bill Zisk, the teacher in charge of Prince Tech's senior electricians in 1999. "Good with their hands. Some of the best natural mechanics I've ever had." But today, not one of the Prince Tech crew has his electrician's license. They need the license, typically obtained in three to five years, to earn about $52,000 a year and protect them from layoffs during tough economic times. One got a college degree but is looking for work. Two joined the military. One's in prison. One works at a car wash, another as a handyman. Of the four still in the electrical field, two have not been able to pass their licensing exam, while the other two haven't finished the training required to sit for the test. In some ways, their failure to get licensed is the failure of Prince Tech. It also represents a broader educational crisis plaguing technical schools across the nation, which are facing increasing federal pressure to raise academic standards and help American businesses compete in a global marketplace. While some of the Prince graduates chose to leave the field, others say they would not have failed the licensing exam if they'd had better math and English instruction at Prince. Some claim some of their shop teachers did not know how to control or reach students. And some say the school did little to help them land trade jobs. A.I. Prince Technical High School regularly ranks at or near the bottom of any comparison among Connecticut's 17 state technical high schools. Students score poorly on state math and reading tests and national vocational exams. And the system as a whole fares only slightly better. Fewer than one out of five of the system's 1999 electrical shop graduates have gotten an electrician's license. Prince is one of six schools that have yet to produce a single licensed electrician from the Class of '99. The failures of the electrical shops are mirrored in many of the technical high school programs, where few seniors can pass written national trade exams or state reading and math tests. The technical schools' new superintendent, Abigail L. Hughes, is the first to admit the system is broken, haunted by low academic performance at many of the schools. She's been working to reform the system, raise admission standards, bolster math and reading instruction, hire better teachers and improve teacher training. The changes are coming quickly. But they're coming too late to help the 1999 electrical graduates of Prince Tech. The Class Of '99 Five years after leaving Prince Tech, Bertrand Edward, the shop's lone college graduate, is looking for work as a school guidance counselor. Jose Viera and Carmelo Serrano, known as the shop's heartbreakers, joined the military. Albert Deleon, the guy who loved fast cars, works at a Hartford car wash. Freddie Resto, the one who would stay up all night playing video games, is a handyman in Groton. Class clown Ziggy Rosario is in prison for dealing drugs. Damion Murray and Jamal Nasrudeen, hard-working sons of immigrants, have good jobs in the field, but can't pass the electrician's exam. Paul Russello has worked for four different electrical shops. It's likely that Ray Lopez, the son and brother of union electricians, will be the first of his class to get his license. Most union apprentices pass the state exam on the first try. If Lopez passes in May, he says, it will be because of what he learned in the union, not Prince Tech. The Hartford native said he's not bitter, but he is blunt. "I am where I am because of my dad, my brother and the union, not Prince Tech," Lopez said during a recent break from an evening trade theory class that all union apprentices attend. "If Prince Tech was all I had, I'd be flipping burgers." But Bill Chaffin, Prince Tech's new principal, said faculty members do the best they can with the students they get. Freshmen with fifth-grade reading skills are not uncommon. Some are hungry, live in violent, drug-ravaged homes or are having children. They struggle to graduate, much less master a trade, especially one as complex as electrical. Their gritty stories unfold in a dingy, rundown building that is waiting for a renovation project envisioned when Ray Lopez was still a child. The school has no quiet classroom where students can learn electrical theory. Fist-sized holes pock the electrical shop's only whiteboard. Shop lights flicker on and off. Chaffin believes a new building and Hughes' new initiatives, especially the math and reading labs launched this year, will make Prince Tech strong. "We're making great strides," he said. "But it is going to be a very long road." `Oh Man, The Math' Damion Murray strolls through the chaotic construction site with heavy tools hanging from every belt loop, a diamond earring hanging from both ears and hard-bitten tradesmen hanging on his every word. He is an apprentice who has failed the state license exam three times, but a single word sprawled on his hard hat - "superhero" - hints at his status among coworkers. The men laugh at his jokes as he figures out where the architect of the new science wing at East Hartford High School wants him to put electrical boxes. His boss, Tom Beaudoin, a Prince Tech alumnus who owns T&T Electrical Contractors Inc. in Hartford, says the 25-year-old apprentice is one of his best electricians, licensed or not. "Life is good," Murray says while he installs a digital clock. "I work inside where it's warm. I make good money. I got my own place, with new furniture. I buy a new car every two years." The handsome East Hartford man is talented, easygoing and diligent, but he lacks the ninth-grade math skills needed to get into the local electrician's union or pass the all-important state electrician's exam. He raised his score from a 44 to a 52 to a 54, but he needs a 70 to pass. Murray can't seem to calculate things such as electrical loads and wire capacity. He calls it "a test problem, not a real-world problem." It's a skill Murray admits he never mastered, even when he was at Prince Tech. Although he didn't study for his first test, he says he's studying now. "I'm a good electrician," he says. "Ask my boss. ... He knows I know what I'm doing. But the math, oh man, the math, it's killing me." `Forgot Our Brains' Murray isn't the only one from his old shop who can't pass the state exam. Nasrudeen, who works with Murray at T&T, has failed three times. Nasrudeen can't finish the test in the allotted time because he can't read fast enough. Nasrudeen says getting his electrician's license would mean an extra $4 an hour on most jobs. On government projects, his pay would almost double. "That buys a lot of diapers," says Nasrudeen, who is eagerly awaiting the birth of his second child. The answers he needs are buried in the National Electrical Code, which can be used during the test, but the manual is as thick and as dull as a Kansas City phonebook. Nasrudeen's well-worn copy is underlined and highlighted. He studies it a few minutes each night in his neatly manicured duplex in Hartford's South End. It doesn't help that English isn't Nasrudeen's native language. The earnest Guyanese native came to the U.S. 11 years ago, when he was 14. Prince Tech represents a wasted opportunity for Nasrudeen. He had a chance to learn a trade for free. Now he will have to pay $400 to $800 for a license prep course just to pass the state electrician's test. Nasrudeen hated high school theory class, where teachers spouted abstract ideas that seemed to have no application in the real world, but he knows his failure to master those lessons, as boring as they were, is hurting him now. "They taught us how to use our hands," he said. "We forgot our brains." State records show that more than a third of 1999 tech graduates who took the state electrician's exam failed it. Most who failed did poorly on the parts of the exam that require calculations and code book references, records show. When Beaudoin attended in the late 1970s, Prince Tech still had difficult entrance exams and accepted only the best students who were determined to become licensed electricians, carpenters or machinists, he said. "Getting into Prince Tech was an honor," he said. "You were somebody." Now, lackluster academics limit the number of licensed electricians and strong college applicants who come out of the state's technical schools. It also leads to lower standardized test scores. And poor test scores have hurt the system's reputation, making it hard to attract top-notch recruits and a racially diverse student body at a time when Hughes wants to raise admissions standards. On Their Own Jose Viera thrived at Prince Tech. The Newington teen ran cross-country and track. His silky voice and playful smile got him a lot of attention from girls. His I'll-try-anything-once philosophy made electrical shop an adventure. Viera was 19 when he graduated. Though bills from the birth of his son, Nathan, were mounting, he was not worried because he had his trade. But getting the trade job that Prince Tech had promised turned out to be hard. "They didn't have much career counseling," Viera recalled. "I found my first job in the classifieds. It took months of calling up place after place after place. In the end, I took the first electrical job I could find." He worked one year at RCI Electrical in Newington, but he didn't like it. It had little in common with what he had liked about electrical shop - where he felt he was always learning something new and enjoyed the camaraderie of classmates - and he hated working outside in the cold. Like most of his classmates, Viera chose electrical shop way back in ninth grade with little thought of what it would actually mean to do that for a living. He stuck with his boys, plain and simple. In the summer of 2001, Viera quit RCI and enlisted in the National Guard to earn money for college. He wanted better for himself, he said. He enrolled in Manchester Community College in 2003 to study forensic science. "I'd always wanted college, but you didn't hear much about that at Prince, probably because none of us had any money," said Viera, who dropped out of the community college after a semester when his Guard unit was called up for active duty. When he is not on active duty, Viera installs expansion joints on power plant smokestacks for Industrial Air Flow Dynamics Inc. of Glastonbury. But his electrical skills come in handy when he is building and blowing up bridges in the Connecticut National Guard's 250th Engineering Unit. "Lots of blueprints," he said. "Plus, I guess it's a good idea to have someone who knows something about electrical theory wiring the C-4. I probably wouldn't be handling the explosives without Prince Tech." Looking back, Viera wishes Prince Tech had organized field trips to different electrical job sites and offered more out-of-school production jobs. And somebody should have at least mentioned college, he said. When Beaudoin graduated from Prince in 1979 and went on to Boston University, students could expect that and more. "Our shop instructors lined us up with jobs," Beaudoin said. "Not just the top guys, although they got the best ones, but everybody. Now the kids are on their own." `Not Bad, Just Bored' Albert Deleon was a class-cutting, out-of-control teenager who got away with everything at Prince Tech. He'll tell you all about it as he makes change for a customer at the Mr. Sparkle Car Wash in Hartford's Parkville neighborhood. He has worked out of the small, windowless booth at this popular Latino hangout for five years. He now manages a small staff of car washers. "It ain't a big-time job or nothing," he said, "but it's all right for a guy who can't drive." For years, Deleon was part of the local street-racing scene. He lost count of all his traffic tickets, but he had always gotten off with a small fine. "I wasn't bad, just bored," he said. "Minor stuff." That was until Deleon got drunk and cracked his car in two while running from a race night police raid. This time, the judge came down hard. He served 30 days in jail - "the hardest days of my life," he says - and won't get his driver's license back until 2008. That ended Deleon's dim hope of becoming an electrical apprentice. Electricians, especially green ones, must drive to jobs all over Connecticut. Deleon doesn't blame Prince Tech for his problems. He doesn't know if any amount of interventions, detentions or suspensions could have saved him. "The teachers didn't bother with me," Deleon recalled. "I liked it like that." He loved wrestling or playing basketball in shop. The only disciplinarian was a teacher famous for his ability to drop a boy to his knees with one jab to the back. But mostly, Deleon recalls teachers hiding out inside air-conditioned offices, venturing out to take attendance or assign homework he never did. Most shop instructors arrive at a state technical high school with a good deal of experience in their trade but little to no formal training on how to teach. They may know how to wire a baseball stadium but have no clue how to manage a classroom or reach students with a range of abilities or learning styles. Mr. Z's Rules Bill Zisk was an exception. When Deleon was a senior, Prince Tech hired Zisk to take over the electrical shop for a year. Zisk grew up in public housing. His widowed mother struggled to pay the bills. He was no stranger to urban poverty and violence when he arrived in Hartford. Mr. Z ran a tight ship. No cursing on the job. Shirts had to be tucked in. No sagging pants, even if it meant the boys wore belts made out of electrical wire. At first, they hated Zisk, whom they called The Warden, with his new rules and his weekly meetings to discuss personal progress. But a truce was declared by the second week. "I showed them respect," Zisk said. "They liked that. Then, what do you know, they got better, and boy, they really, really liked that." By the end of the year, Zisk had the kids painting the electrical shop in the school's trademark purple and gold and wiring the welding shop. "Little Freddie" Resto remembers that Z could break even the most complicated electrical theory down into small and seemingly simple parts. When Zisk gave the seniors a day to take his own version of the state electrician's exam, every one of them passed it. At the end of the year, Zisk accepted a permanent teaching job at Vinal Tech in Middletown. "We learned a lot from Z, even though we didn't want to," Deleon recalled as he was showing an off-roader how to wash a muddy Jeep. "Maybe we'd always wanted to learn, deep down. Who knows? For one year, he got to us." Union Man Even when Ray Lopez is laid off, which happens every now and then, he still earns more from a week's unemployment check than Deleon does from a 60-hour week at the car wash. A union man definitely has an edge, Lopez said. Lopez's dad wanted him to go to college, but when Lopez decided to "stick with what I know" and get into the family trade, his dad and his older brother, who belong to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, started preaching the benefits of a union life. "It was union this, union that," Lopez said. To persuade Lopez, who was reluctant to sign up for the union's intensive training program, his brother and father showed him their paychecks. "The money got pretty good pretty fast." In Connecticut, someone who wants to become an electrician must find an employer willing to train an apprentice in a program of electrical studies and work that is outlined by the state Department of Labor. Some opt to join one of Connecticut's four electrician's unions. The nonunion contractors require their apprentices to meet state guidelines through a three-year program, but the union courses are five years long. Upon completion, the apprentice takes the state license test. State regulations exempt technical school grads from electrical studies. Although this seems like a perk, some state officials believe the three-, four- and five-year gap in theoretical schooling hurts them when it comes time to take the state test. The unions require apprentices, tech school grads or not, to complete five years of education, including hands-on training at different jobs during the day and twice-a-week electrical theory classes at night. Lopez says he learns best by doing. He didn't respond well to Prince Tech's drill-and-kill style of teaching. He yearned for hands-on work, but he knew that he needed to beef up his knowledge of electrical theory to get his state license. "I needed to see the theory in action to really get it," Lopez said. The union's mix of daily work and nightly theory seems to work. Over the last five years, only two of the 70 apprentices coming out of the Hartford union have failed the state license test. Those two passed on their second try. But most Prince Tech grads can't even make it into the union. Each year, Prince Tech sends a bus full of students to the union hall to take a basic math test used to evaluate would-be apprentices. Most years, nobody passes. Lopez plans to take the state electrician's exam in May and expects to pass. Everybody at Prince Tech always thought he'd be the first one. He had ambition. And it doesn't hurt that when you shake his family tree, an electrician falls out. "Books are hard for me, always have been, but give me half

a chance and I'll make good," said Lopez, who is saving

up to buy a townhouse. "I ain't afraid to work. I'll get

my hands dirty. Just give me a chance to take my shot."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 | |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jamal Nasrudeen

Jamal Nasrudeen